So, you want to be a cop?

CLAY COUNTY – The biggest fear of any police officer is silence, especially after a physical confrontation with a suspect who’s considered violent.

When Clay County Sheriff’s Office and …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, or purchase a new subscription.

If you are a current print subscriber, you can set up a free website account and connect your subscription to it by clicking here.

If you are a digital subscriber with an active, online-only subscription then you already have an account here. Just reset your password if you've not yet logged in to your account on this new site.

Otherwise, click here to view your options for subscribing.

Please log in to continueDon't have an ID?Print subscribersIf you're a print subscriber, but do not yet have an online account, click here to create one. Non-subscribersClick here to see your options for subscribing. Single day passYou also have the option of purchasing 24 hours of access, for $1.00. Click here to purchase a single day pass. |

So, you want to be a cop?

CLAY COUNTY – The biggest fear of any police officer is silence, especially after a physical confrontation with a suspect who’s considered violent.

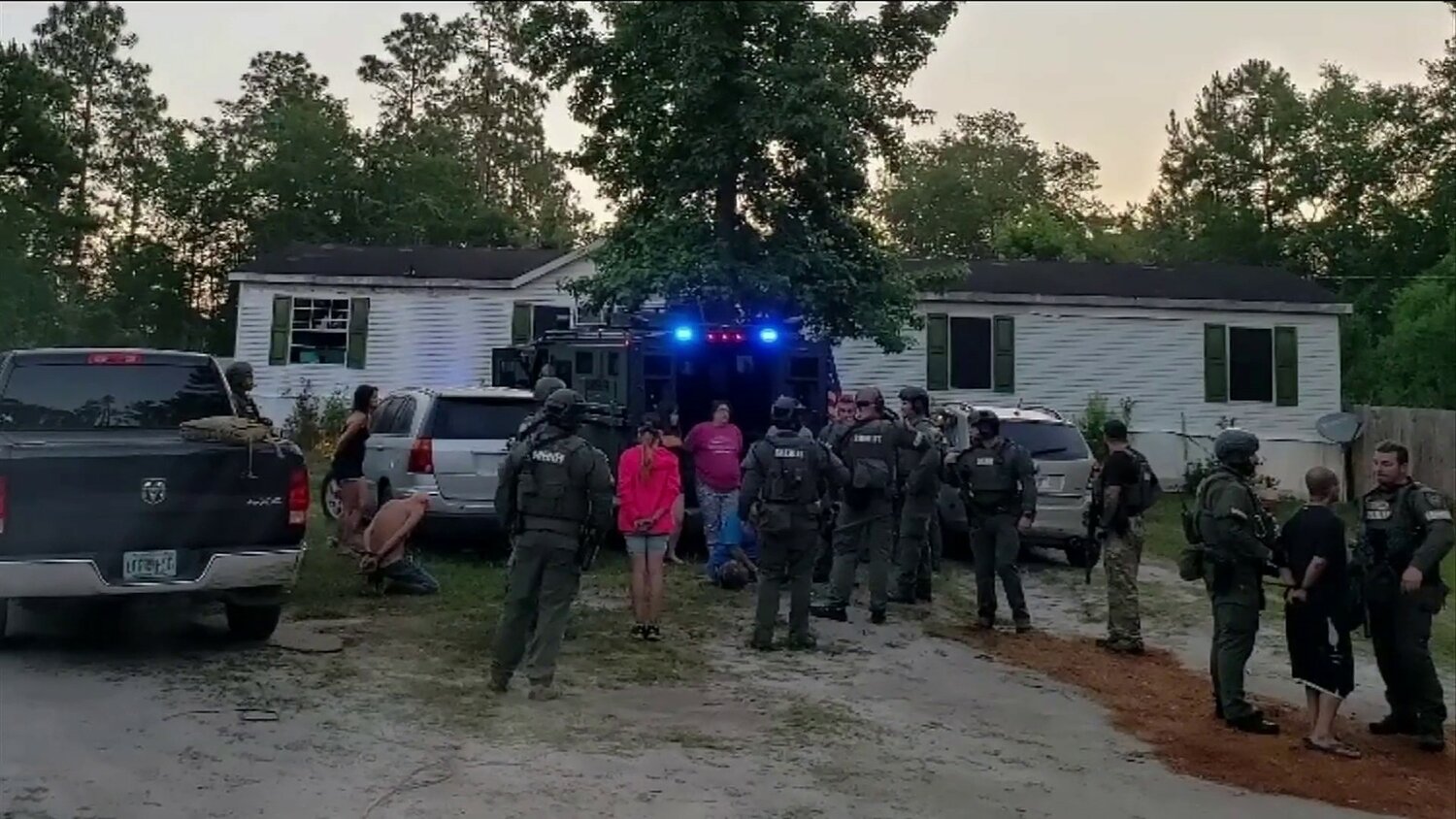

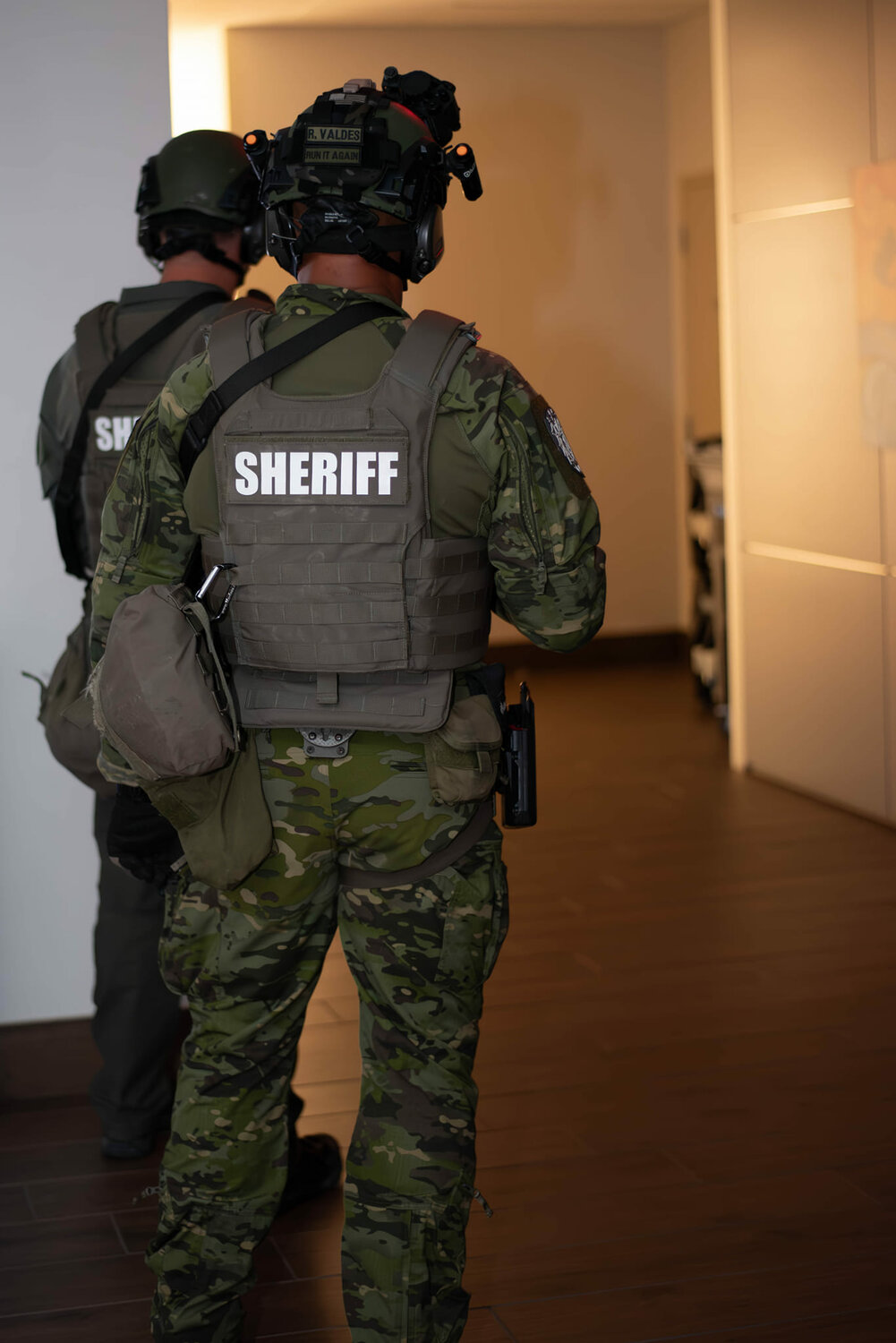

When Clay County Sheriff’s Office and Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office deputies jumped into the murky waters of Little Black Creek on a Sunday afternoon after chasing a man suspected of an armed carjacking and home invasion, the law enforcement agencies finally wrestled control of the 19-year-old in the chest-deep creek.

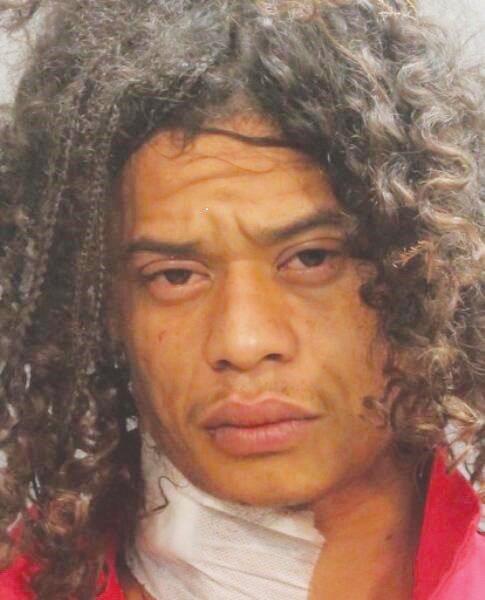

One deputy didn’t immediately answer when the command tried to account for everyone. They knew he went into the water, but they didn’t see or hear from him for more than a minute after Carlos Matute was drug away in handcuffs. Just as confusion turned to fear, the deputy finally keyed his microphone and said he was wet and cold, but all right.

Not knowing is the biggest challenge of being in law enforcement.

“It’s never what you want to hear,” said Sheriff Michelle Cook.

Every day, the men and women of law enforcement face some of the worst society has to offer. The job is both rewarding and complicated. There are sights and skirmishes the public doesn’t know.

Being a cop isn’t limited to a 10-second cellphone video on the local news. It’s patience and restraint. It’s compassion and compliance. It’s a high-five from an elementary student walking home from school and a hug from someone whose problem was quickly resolved.

It’s also chasing criminals through parking lots. It’s listening to lies and fake stories. It’s the combative driver who’s had too much to drink. It’s the overwhelming sense of helplessness and urgency when a child goes missing.

“Being a cop isn’t a job,” said Orange Park Police Lt. Cody Monroe. “Being a cop is a calling.”

Statistics show that in the last 30 years, at least 40% of law enforcement officers quit in the first five years, Sheriff Michelle Cook said.

“The workforce is dwindling,” she said. “You can train somebody for what they’re going to see, smell or hear on the job. We’re like companies who have to do more with less.”

Cook said 70% of her deputies have less than five years of experience.

Agencies rely on technology to keep pace with criminal ingenuity and fill the void. Traffic cameras and license plate readers are installed throughout the county. Green Cove Springs and Orange Park have red-light cameras. Many businesses and some residents can link their surveillance to the sheriff’s office’s Connect Clay County program, allowing dispatchers to get real-time information when a crime has occurred.

Two other vital tools are cellphones and doorbell cameras. Cellphones can be tracked, and home cameras often catch a suspect committing and leaving a crime.

But the most effective tool is a deputy or police officer on the beat, where they can create relationships and garner valuable intelligence. It also puts them face-to-face with bad people.

“If we’re involved in a situation where we have to go hands-on with somebody to place them under arrest, emotions can seem to be high or high-strung, or a kind of no-nonsense type attitude,” CCSO Sgt. Zach Cox said. “You never know what (a deputy) has dealt with in the past. Seven hours earlier, they could have been on a death scene. They could have been to a traffic fatality crash, and their range of emotions is just all over the place. Then you get the one person who has a warrant and doesn’t want to put their hands behind their back, and they’re amped up.

“It takes a special person, a special demeanor, to be a deputy,” Cox said.

Clay Today poured through the arrest reports during a three-week timeframe, starting on Jan. 23 and ending on Feb. 13. The numbers tell just how difficult their jobs can be – five counts of attempted second-degree murder of sheriff’s office deputies, 15 cases of resisting, obstructing or opposing arrest, four counts of felony fleeing with lights and sirens active, three counts of aggravated assault against law enforcement and one count of battery to a jail deputy.

Those who get past the first five years said the job is rewarding. The challenge is building experience, expanding training, learning tolerance and learning to be numb to man’s indiscretions.

“There are few other professions out there that give you the opportunity to make such a difference in the world,” Monroe said. “You’ll never be rich. You’ll not likely be famous. But I promise you, when you prepare to leave this world and move on to the next, you’ll never have to worry about whether you made a difference.”

Sheriff’s Office Sgt. Ed Kroh said veteran officers become immune to horrific scenes. It’s why few talk about the details of their shifts. And most need an hour or two to “de-compress,” another deputy said.

Kroh said he found a child who had been severely mauled by a pit bull on his first day on the job. Others have seen the results of a suicide or traffic accident.

And most, if not all, have had to use their training in a “hands-on” situation.

“I mean, you graduate the police academy with a certain demeanor,” Cox said. “After the police academy, you’re just excited to put on the uniform, so it takes time, years of service, to grasp a different demeanor and a way to put it into effect in a good way.”

Even when the suspect is armed and on the loose.

Matute broke into a couple’s home at 3 a.m. armed with a handgun on Dec. 3. He then stole the couple’s car, according to JSO, before starting an intensive search that lasted 12 hours and involved JSO, CCSO and the Florida Highway Patrol. Matute abandoned his car at a storage facility on Blanding near Henley Road before running through backyards along Henley Road for nearly two hours. He fought with deputies and K-9s before being taken into custody.

“It turned out OK,” Cook said. “That’s the way we want it to end. Everybody got to go home that night.”

Only to get up the next morning and do it all over again.