Indigo: Clay County’s first cash crop

Clay County History

CLAY COUNTY – 1763 The Treaty of Paris ended the Seven Years War between the British, French, and Spanish. England took Canada from the French. Havana was captured by the British and returned …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, below, or purchase a new subscription.

Please log in to continueDon't have an ID?Print subscribersIf you're a print subscriber, but do not yet have an online account, click here to create one. Non-subscribersClick here to see your options for subscribing. Single day passYou also have the option of purchasing 24 hours of access, for $1.00. Click here to purchase a single day pass. |

Indigo: Clay County’s first cash crop

Clay County History

CLAY COUNTY – 1763 The Treaty of Paris ended the Seven Years War between the British, French, and Spanish. England took Canada from the French. Havana was captured by the British and returned to Spain in exchange for Florida. Florida was then divided into two parts: British East Florida and British West Florida.

With St. Augustine as its capital, British East Florida stretched from the Atlantic Ocean to the Apalachicola River. British West Florida, with Pensacola as its capital, reached from the Apalachicola River to the Mississippi River. The land between St. Augustine and Pensacola was wilderness.

Hoping to attract investors and settlers to the area, the British began giving citizens land grants. Some grant holders were absentee owners, while others were speculators. Some were hands-on owners, however, who endeavored to create successful plantations in the new colonies. Indian hostilities were not an issue anymore, as the British had signed a treaty promising not to colonize west of the Appalachians. The demarcation line ran north and south through the western side of Clay County.

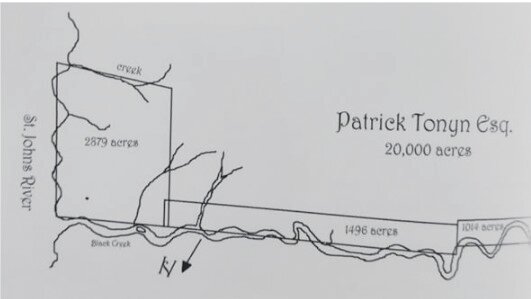

Meanwhile, the economy was on fire. Some of the grants in present-day Clay County numbered 20,000 acres each. They stretched some 20 miles south from near what became NAS Jacksonville and ran upriver towards Palatka in Putnam County.

During this period, several large indigo plantations surrounded Doctor’s Lake, and many others graced the shores of Black Creek and the St. John’s River. The plantations had lovely names like Spring Garden, Tobacco Bluff, Laurel Grove, and Harmony Hall. Indigo was inexpensive to cultivate and worth its weight in gold.

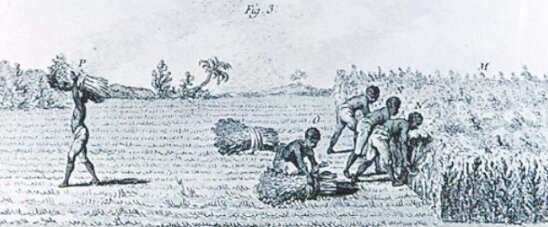

The British enthusiasm for indigo in Florida led planters to import thousands of slaves to tend the crop. As with other labor-intensive crops (sugar cane, rice, cotton), indigo cultivation caused laborers to suffer. It was hot, smelly work. Indigo vats stunk of rotted vegetation, much like the vase water of a rotted floral bouquet. Yet, the brilliant blue dye it produced was a beauty to behold.

Indigo grew wild in Florida, but the plantations tended to grow several imported species. The best indigo was called flotant, also called flora. The paste it made dried easily and was a dark blue, lending towards a violet hue. The next grade down was called violet, and both types were used for dying cotton-based cloth and linen. Indigo production smelled terrible due to the putrefying plants filling the vats. It was so offensive that the vats were at least a fourth of a mile from houses. The smell drew flies by the thousands, which created a serious risk of disease. The flies even attacked the livestock on the plantation, making life miserable for man and beast alike.

“Uncommon swarms of flies, gnats, and other insects, which attend putrid air, and unhealthy places covered with wood; the first of these is not common here, except at indigo works; and if these, according to my former caution be little remote from the dwelling, I never saw nor heard of any bad consequences with regard to health attending them. I have already mentioned the bad effects of these voracious vermin on cattle of all kinds at an indigo work; gnats, here called mosquitos, are vastly numerous in some spots.” Said Bernard Romans, an 18th Century Dutch-born navigator, surveyor, cartographer, naturalist, engineer, soldier, promoter and writer who worked in the British American colonies.

The process of making indigo dye is not complicated, but it does require skilled workers. During the twenty years of British occupation, Florida plantations exported significant quantities of indigo, citrus, sugar, and naval stores, all through the hard work put in by enslaved peoples. Slavery existed under Spanish rule, and African slavery became more prominent after the British took control of Florida. It came to a point when there were more enslaved people than colonists.

Indigo production was a labor-intensive process. The plants needed loose soil (Florida has lots of sand), hammock-style soils (moist) and a flat, level field. Getting the soil right was imperative to getting a good first crop. About four bushels of seed were required for one acre. Sowing the seed was done March through May, as that was the wet season, and crops could be harvested three to five times a season between May and November.

Farmers harvested the best dye with the first cutting. After the third year, the poor quality of the dye meant replanting. Indigo is a legume; all it needed was the addition of phosphorus to the soil to yield well. Indigo was grown for dye, to enrich the soil, and to feed livestock. It only had two enemies, drought and caterpillars. Water was not an issue in Clay County, as all the plantations here had access to creeks, lakes, springs, and wells. Caterpillars were hand plucked from the plants and crushed.

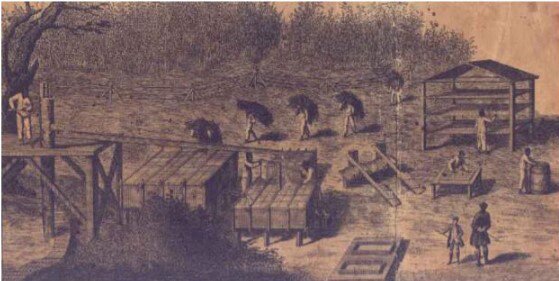

The cut plants were placed in a vat with water and then pounded with wood staves to break the plants down. English planters used water mixed with lime. The mixture was allowed to ferment for up to twenty hours. Once the fermentation began, the mix became bubbly, thick, and turned purplish-blue. The now-smelly mix had the plant material removed and was churned by hand by slaves. Buckets were plunged repeatedly up and down into the indigo until the indigo paste separated from the water. This was a messy process, and it turned the hands of the workers a permanent shade of blue. The paste settled to the bottom of the vat and the water drained. The paste sat there for an additional eight to ten hours before being strained through a horsehair sieve. Next, the paste was either poured into conical cloth bags called “Hippocrates sleeves” and hung in the shade to dry or spread out on trays under a drying shed. No sunlight could touch the indigo at this stage, as it would destroy the dye. Once the paste was completely hard and dry, it was cut into squares. These squares were carefully turned three to four times a day to make sure that they were completely cured. Also, the flies had to be driven away from the paste all day and all night, as they would damage the indigo.

The third and last governor of British East Florida had a very successful indigo plantation around Magnolia near Green Cove Springs. His “large and commodious” frame house with plaster walls is believed to have been situated where Camp Chowenwaw is now. When William Bartram visited Patrick Tonyn’s plantation, he took note of the quality of the indigo crop. Bartram said he was shown “some samples of the best flora Indigo [he] had yet seen, there were twenty hands employed on this plantation who made about twelve hundred [weight] of indigo the last year and had now planted this year’s crop.”

Florida could produce multiple crops of high-quality indigo each year. By 1769, the indigo harvest totaled more than 6,000 pounds. The peak of production was in 1776, when 58,300 casks were exported. By 1778, the exported amount was cut in half due to the depletion of the thin, sandy soils. In 1786, the fate of indigo production in the Americas was sealed when the British East India Company dumped 250,000 pounds of indigo into the market and crushed the plantations into oblivion. By 1810, the company was capable of placing 5.5 million pounds of indigo into the market per year, and the price of indigo bottomed out. None of this mattered to the British plantation owners in Clay County since they had long fled Florida in 1783 when Britain ceded Florida back to Spain.