'Bridging the Reading Gap' one child at a time

One local business aims to teach children how to read

kyla@claytodayonline.com

FLEMING ISLAND - Reading is a fundamental skill. It determines the way you learn, act, and communicate your way through the world. But, it is also a skill that is not afforded to everyone. …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, below, or purchase a new subscription.

Please log in to continueDon't have an ID?Print subscribersIf you're a print subscriber, but do not yet have an online account, click here to create one. Non-subscribersClick here to see your options for subscribing. Single day passYou also have the option of purchasing 24 hours of access, for $1.00. Click here to purchase a single day pass. |

'Bridging the Reading Gap' one child at a time

One local business aims to teach children how to read

FLEMING ISLAND - Reading is a fundamental skill.

It determines the way you learn, act, and communicate your way through the world.

But, it is also a skill that is not afforded to everyone.

Reading disabilities are a common occurrence, especially in young children.

As a former school teacher, reading specialist, and educational advocate, Danyse Streets vows to help change this one child at a time.

In July of 2021, Streets created Bridging the Reading Gap to help children in her community develop this important skill.

“To be honest, if you can’t read, you can’t do anything,” Streets said. “You can’t do math, you can’t do science, you can’t do history. So, for our kiddos who are being put out into the world as functionally illiterate adults, it is completely disheartening to me.”

Bridging the Reading Gap is a two-pronged approach to solving this problem. By providing tutoring, parents can have their kids screened to see where their abilities lie. Streets said she tests the children to dig deeper into their deficits and figure out exactly what they need.

Streets also offers advocacy services, being a voice to families that need it and helping with any further resources.

Primarily, Streets said she tends to tutor children who have reading disabilities like dyslexia, which remains one of the most common types of learning disabilities.

Streets uses the Orton-Gillingham method of teaching, which is a form of direct and systematic reading instruction. It covers phonics, phonemic awareness, phonological awareness, oral reading fluency, and coding.

On Mondays and Wednesdays, Streets works from her home with children 5 to 14 to help with their efficiency in these areas.

“I have kids who are technically fifth graders who came to me reading on a kindergarten, first-grade level,” Streets said. “So, they vary in ability, and range, and age, and grade level. But, really my primary job is literally just teaching them how to read.”

Streets said watching her own daughter’s struggles made her want to find a way to help.

When Streets’ daughter entered the VPK age, Streets said she noticed she wasn’t quite where she needed to be. Streets noted that although she was a former teacher, her daughter struggled.

“I knew it wasn’t typical reading struggles. I could tell it was more than that,” Streets said. “And so I had read with her and sang songs with her, and practiced rhyming with her, and practiced letter games and sounds and she just didn’t seem to get it.”

Streets realized that the public school system would not give her child the direct help she needed, so she began looking at private schools.

“The private schools didn’t want her because while she was sweet and adorable and funny, she couldn't pass their admission exam,” Streets said.

After finally finding a school that would fit her daughter’s needs, Streets said she still only knew about 12 letters and sounds by mid-kindergarten.

“We started private tutoring at the school on top of paying tuition for school. And she made some gains,” Streets said.

When the pandemic hit, Streets said being at home together, made her realize the magnitude of just how much her daughter was struggling.

“[I] realized that she was just having significant struggles in the area of reading and math, spelling, and writing,” Streets said.

At the end of her fourth-grade year, Streets said it was determined that her daughter was dyslexic. After much back and forth within the school system, Streets ultimately began homeschooling her.

At that point, she said she realized that other private, public, and homeschool students may be struggling like her daughter.

“I started taking some pretty intensive training and attending conferences and workshops,” Streets said. “To really beef up my skills and to offer tutoring to families of kids with similar profiles to her.”

Since taking the huge step, Streets said it’s been nothing but word of mouth. But she is proud of how much Bridging the Reading Gap has grown — so much so that she has since branched out into educational advocacy as well.

“I also advocate for many families in Florida. In Clay County, Florida counties and across the country, helping them,” Streets said. “I’ve helped many of the homeschool families I tutor get their kiddos tested either through the county or privately.”

Streets added that she also helps families apply for the ‘Step Up For Students’ scholarship, allowing them to cover their tutoring.

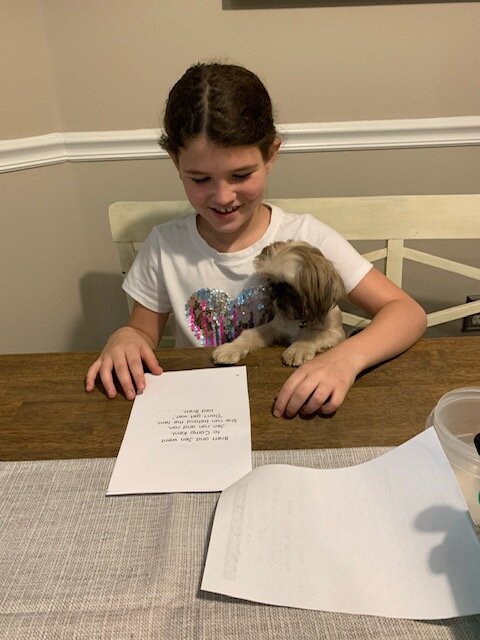

Sarah Payne said that, as a homeschool parent, she was unaware of the resources available until she began working with Streets.

When Payne began bringing her daughter, Annie, to Streets, she said she was able to get the assistance that she desperately needed. Payne said that Annie was even finally able to get tested to see if she had a disability.

“She fights for these kids, and they know it too. Annie will tell you that Danyse is one of her favorite people," Payne said. "She helped her when I couldn’t help her."

Since bringing her daughter to Streets, Payne said she has seen so much improvement with Annie.

“Annie has learned so much. Danyse even went as far as to take a book, ‘The Logic of English,’ and she broke it down because Annie’s a very literal person,” Payne said. “So, she needed to know why things were how they were.”

Frances Frias has been bringing her son Xavier to Streets since kindergarten. She said Streets had made a tremendous difference in her son’s reading ability, even having him read on a first-grade level within just a year.

“For me, that was an amazing experience to see my son go from not being able to identify letters or letter sounds, to all of a sudden reading on his own,” Frias said.

Streets said that she thinks one of the big problems that public schools face is the

curriculum.

“We have a Tier 1 curriculum problem,” Streets said. “I think if we can give them the foundation that they need in phonics and phonemic awareness, and those basic reading skills, we would have a significant drop in children who needed IEPs and extra help.”

Being an advocate for children’s education is something Streets said she will continue to do. Because for her it’s not just a passion, but her absolute purpose.

Being able to read is a privilege, and she said she believes every child deserves it all the same.

“I would love for every child to learn to read,” Streets said. “And, for more people to support that within our legal system, the people in charge of education in our country… [and] our counties.”